‘Time’s a Wastin’: The Enduring Teaching Legacy of Sara Crawford

Sara Crawford died at 97. I made a point of checking in once a year to see how she was doing. Sadly, my timing was off. She had passed away in September and I had missed her memorial service. Teaching the piano was her driving force and she continued until the end of her life.

Sara was my teacher during the season of my life when I decided to make the piano my profession. Twice a week I would take the train into the city and go to her apartment on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. An English breakfast tea and almond croissant from the patisserie downstairs were necessities. For the next three hours, we would go through scales, Hanon exercises, Czerny studies (which I loathed then and now), Sonatas, Fugues, Études, and Concerti. About 90 minutes in when I started looking peaked she would ask, “Do you need to take a walk around the block?” I would politely decline and we would soldier on.

My training up until this point had been uneven at best. Sara taught me how to voice a chord so the top tone pierced the air and lower voices supported it like a blanket. How to shape my hand to have the power of a boxer and the delicacy of a lacemaker. How to shape a melody to cause the listener’s heart to race and then take their breath away. I learned my first complete Beethoven and Mozart sonatas, my first Bach Prelude and Fugues, my first Chopin Ballade and Scherzo, my first Debussy Preludes, and my first Brahms Intermezzi. She introduced me to Samuel Barber, Olivier Messiaen, and Arnold Schoenberg.

Most importantly, she taught me to think. “There are brilliant pianists who play marvelously, and yet they can’t explain anything they do. You need to be able to explain every note and every gesture.”

Sara was born in 1926 in rural Sunnyside, WA. A powerful, vigorous woman with huge hands I assumed she was 10 years younger. She never lost her heavy Pacific Northwestern accent, but she was a New Yorker through and through (“Are there cows here?” she once asked me arriving in suburban Connecticut). Washington was too small for the enormity of her passions and talents.

Sarah lived in apartment 6126 of the Ansonia building from 1959 until her death. Said to resemble a giant birthday cake the building’s housed Florence Ziegfield, Sarah Bernhardt, Gustav Mahler, Igor Stravinsky, and Babe Ruth.

In the late 60s when New York was rough and tumble “The Continental Baths” a gay bathhouse took up residence in the basement. “Bathhouse Betty,” better known as Bette Midler, was the entertainment with Barry Manilow on the keys. Its thick walls proved ideal for musicians. Pouring out of the windows came the sounds of opera singers receiving coachings on Verdi (directly across the street from his square with his namesake) and concert pianists preparing for their debuts. Sarah’s apartment overflowed with decades of scores, recordings, mementos, and gifts from students, family, and friends.

One photo near the entrance was of opera singer Joseph Drogheo dressed like a character out of Commedia dell’Arte. He died just a few months before I began lessons. They married in the 60s after meeting at a concert. While she didn’t discuss him in our lessons I could tell from her passion for opera, the Italian language, culture, and people he was the love of her life. She survived him by a quarter century.

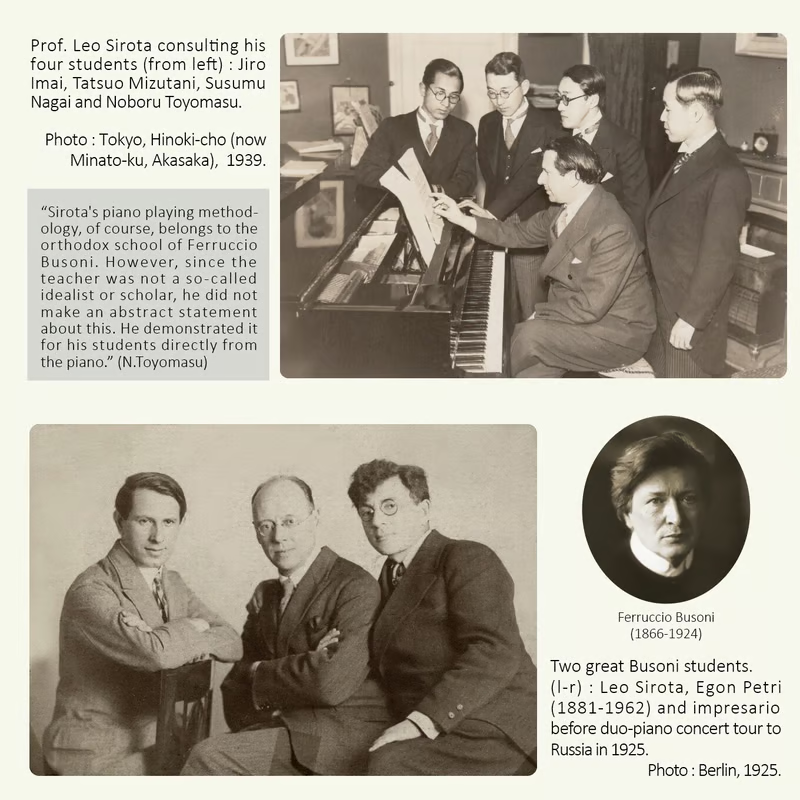

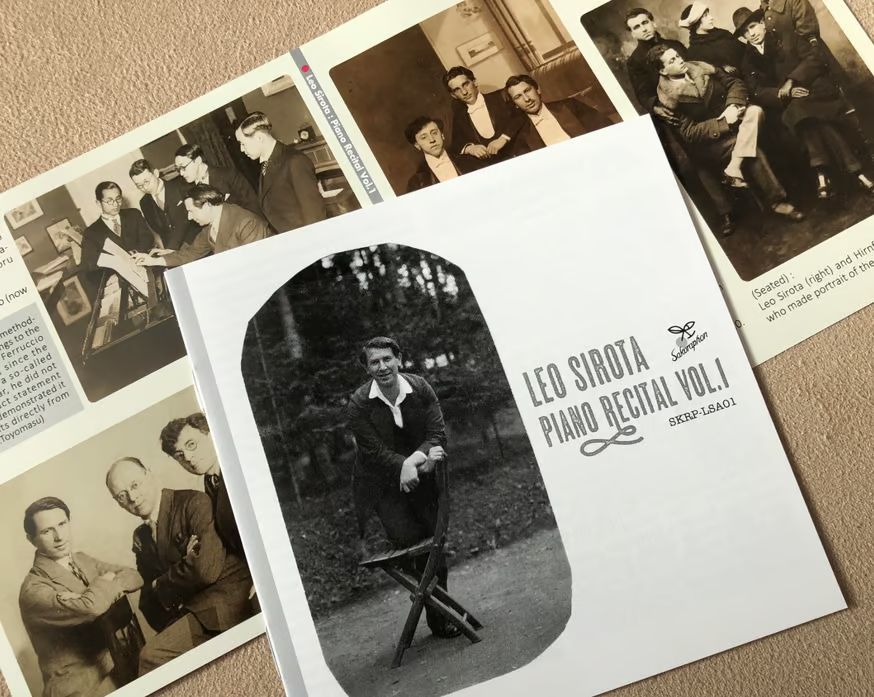

For me, her musical lineage was the link to the past. Leo Sirota was a great Jewish-Ukrainian virtuoso. When his teacher, the legendary Ferruccio Busoni, needed someone to give the Vienna premiere of his monstrous “Piano Concerto” he chose Sirota as the soloist. When Arthur Rubinstein found Stravinsky’s piano arrangement of three movements from Petruška too difficult Sirota gave the premiere. He founded the first conservatory in Japan and his daughter helped to write the postwar Japanese constitution. In 1946 he emigrated to St. Louis, gave his Carnegie Hall debut, and founded a conservatory where Sarah was his pupil.

https://www.thepianofiles.com/leo-sirota/

At Juilliard, Sarah studied with another Busoni pupil Eduard Steurmann. Also a Jewish musician he immigrated to the United States to escape Nazism. He was a close friend of Arnold Schoenberg and premiered two of his greatest works: “Pierrot Lunaire” and the “Piano Concerto.” His students included the pianists Alfred Brendel, Menachem Pressler, Moura Lympany, and Russell Sherman as well as the philosopher Theodor Adorno and conductor Gunther Schuller.

Most dear to her was Carl Friedberg (“he was like knowing a history book”). Friedberg was a prized pupil of Clara Schumann. In the 1880s he gave the first all-Brahms recital having coached with the composer himself. His annotated scores describing how Brahms played his music were donated to Columbia University where he taught after being forcibly retired from Juilliard for being too old. Sadly, they were either lost or stolen. Amongst Carl Friedberg’s notable students was Nina Simone, the “Queen of Soul” who mixed Jazz and Blues with Liszt and Bach in her inimitable way.

https://www.thepianofiles.com/carl-friedberg/

Watching her memorial service at the Hoff-Barthelsen School where she taught for decades (organized by her long-time pupil and colleague Oldrich Tepley), the reminiscences of her students and family ring true. She was both kind and highly demanding. As a sensitive teenager hungry for knowledge this mixture suited me perfectly. Lessons always ran overtime by several hours. She never took an extra penny.

Every student was treated as the star student, even those who didn’t want to be. “The lesson is over when I say it’s over, not when the clock says it’s over,” she told one ornery teenager. The strength of her convictions never failed her. “Some teachers think you should play with your fingers rather than the weight of your arm, but I know I’m right.”

Scores were specially prepared for each student with every fingering and pedal marking written in. She had a pencil case full of colors. Each week would be a new color and after several lessons, the score looked like a toddler had attacked it. Every marking had to be scrupulously adhered to, every physical gesture carefully planned.

Sara wasn’t much of one for chitchat although she did like to reminisce about her Juilliard days. She and her friends would steal keys from the guards to get more practice time until they were finally caught (“you have to fight for your practice space”). When you did receive a message from her, it included a list of the good playing habits she hoped to instill. Each section of the score was given a number and you had to be able to start at any randomly called section should there be a memory slip. She recalled performing a Sonata and taking the ‘wrong exit off the highway’ replaying the exposition on a loop. She made it her goal to ensure her students would never have the same experience.

Sarah only was angry with me once. We were a couple of hours into a lesson late in the evening and I started futzing around with the keys. “I have to listen to children play nonsense like that all day. It’s worth nothing! Times a wastin’.” The message was clear: this was serious business and every minute mattered.

Not surprisingly, Brahms was one of her favorite composers. Sarah encouraged me to see Maurizio Pollini play the Brahms Second Piano Concerto at Carnegie Hall, a life-changing experience (https://youtu.be/3cP5O3USfxk?si=R_oVdf4L_3HvQZ0z). With her help, I played my first large-scale chamber work: the Brahms Horn Trio. A piece she taught to virtually every student was the Brahms G Minor Rhapsody. She found it ideal for teaching the use of arm weight. I loved the piece and still have three copies of it with her copious markings as well as the cassette tape she made for me featuring her favorite interpretations (Lupu and Katchen).

As I write this post, I just gave my final lesson to a graduating high school senior at the same stage of his life. In the fall he heads to the Eastman School of Music. His new teacher there has assigned him a Brahms Intermezzo to work on during the summer. As we untangle Brahms’ dense counterpoint, trace the contours of his melodic arabesques, and speculate as to the hidden passions and regrets embedded into the music, I feel certain that I am passing on a bit of Sarah’s love for music to my student. Just as she was the inheritor of her teachers’ musical gifts so many years ago.